As of May 1 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARSCoV- 2), has spread to more than 200 countries and territories, caused over 3 million deaths, and infected more than 150 million people worldwide [1, 2]. Also by May 1 2021, a third wave of infections was experienced by a number countries, some caused by more infectious genetic SARS-CoV-2 variants [3], even in the wake of mass inoculation efforts made possible by the fastest development of a vaccine ever seen in modern history [4]. Nonetheless, the pandemic continues to lead to social unrest [5] and economic and educational pitfalls [6]. The pandemic has also negatively impacted the provision of health care, and in particular oral health care, due to the close face-to-face proximity of professionals to patients’ face [7]. As the virus that causes COVID-19 can be found in saliva droplets and aerosols, the practice of oral health care is said to be at the highest risk for transmission of the virus [8, 9] even more so in light of a strong evidence for airborne spread as discussed by Greenhalgh and colleagues [10].

Use of Toothpaste and Toothbrushing Patterns Among Children and Adolescents — United States

Fluoride use is one of the main factors responsible for the decline in prevalence and severity of dental caries and cavities (tooth decay) in the United States (1). Brushing children’s teeth is recommended when the first tooth erupts, as early as 6 months, and the first dental visit should occur no later than age 1 year (2–4). However, ingestion of too much fluoride while teeth are developing can result in visibly detectable changes in enamel structure such as discoloration and pitting (dental fluorosis) (1). Therefore, CDC recommends that children begin using fluoride toothpaste at age 2 years. Children aged 3 years should use no more than a pea-sized amount (0.25 g) until age 6 years, by which time the swallowing reflex has developed sufficiently to prevent inadvertent ingestion. Questions on toothbrushing practices and toothpaste use among children and adolescents were included in the questionnaire component of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for the first time beginning in the 2013–2014 cycle. This study estimates patterns of toothbrushing and toothpaste use among children and adolescents by analyzing parents’ or caregivers’ responses to questions about when the child started to brush teeth, age the child started to use toothpaste, frequency of toothbrushing each day, and amount of toothpaste currently used or used at time of survey. Analysis of 2013–2016 data found that >38% of children aged 3–6 years used more toothpaste than that recommended by CDC and other professional organizations. In addition, nearly 80% of children aged 3–15 years started brushing later than recommended. Parents and caregivers can play a role in ensuring that children are brushing often enough and using the recommended amount of toothpaste.

Mindful Dentist

Dental anxiety challenges patients and providers alike, creating barriers to care, increasing pain perception, and increasing the time and effort required to complete treatment. While patient-centered dentistry invites us to care for the person attached to the teeth, many dentists feel ill-equipped to handle the many emotions that arise during dental treatment. Mindfulness and the practices that cultivate it are invaluable to the provision of patient-centered care in four respects: 1) it provides balance to the dental professional during stressful times, 2) it cultivates the qualities of a patient-centered health care provider 3) it guides actions necessary to meet a patient’s needs, 4) it provides techniques that patients can themselves use to find balance during stressful times. All of these fruits of mindfulness practices are demonstrated in three true vignettes of fearful patients who were treated by the author. Video footage of the three stories is also provided.

Vaccinations for Dental Professionals

Widespread immunization has dramatically altered the global landscape for the transmission of many diseases, reducing morbidity and mortality.1,2General recommendations for childhood and adult vaccinations are designed to minimize the risk of disease transmission among the general public.1 In addition, immunization is considered an essential component of infection control and prevention in healthcare settings.3 In the United States, national guidelines on immunizations for healthcare personnel (HCP) are provided by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC).4 State and federal regulations and recommendations from the Public Health Service and organizations should also be included in policies.3 The emergence of COVID-19 and the ensuing pandemic have also resulted in the rapid development of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 and additional recommendations.Immunization is considered an essential component of infection control and prevention in healthcare settings.

Laws and Vaccinations for HCP

Under the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) mandates that all workers at potential risk of exposure to blood or other potentially infectious materials (OPIM) be educated on the risk of transmission, the benefits of vaccination and offered Hepatitis B (HBV) vaccination at no cost and at a reasonable time and place.5 Should individuals decline vaccination, they must sign a declination form that must be kept in their personnel file. Following declination, individuals can later request vaccination should they wish to and must then receive this at no cost. State laws for HCP may also mandate vaccinations against some transmissible diseases.6 Mandates vary by State, facility and the role of HCP, making it important to check for your location. In addition, exemptions are granted on medical grounds, and may or may not be permitted on philosophical or religious grounds.7,8 Healthcare facilities may also have policies mandating vaccinations, for example, dental schools can mandate vaccinations for students before they begin their curriculum.9,10 Immunizing students before they are at risk of exposure when treating patients protects students and helps to protect others in the school environment, including patients.Under the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard, all healthcare workers at potential risk of exposure to blood or OPIM must be offered vaccination against HBV.

Recommendations for routine vaccination of dental healthcare personnel (DHCP)

Vaccination is recommended for diseases known to represent a substantial risk for transmission in healthcare settings. For DHCP, this has included immunization against HBV, measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, tetanus, pertussis, diphtheria and influenza unless as noted an individual is already immune to a given disease or the vaccine is contraindicated for that individual.3 (see Table 1 for contraindications for vaccines) Vaccines against COVID-19 have now been added as a new vaccine.

HBV vaccine

Vaccination against HBV is recommended unless there is documented evidence of a completed vaccine series or there is serologic evidence of immunity.11 As noted above, this vaccination must be offered to DHCP at risk of exposure to bloodborne pathogens. The CDC Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings — 2003, which were published prior to the development of a 2-dose series, recommend vaccination as a 3-dose series to individuals at potential risk of exposure.3 However, in accordance with the more recent CDC recommendations on vaccinations for HCP, which explicitly includes DHCP and students, HBV vaccination can be given as a 2-dose series with the doses 1 month apart (Heplisav-B) or as a 3-dose series at months 0, 1 and 6 (Engerix-B or Recombivax HB).11

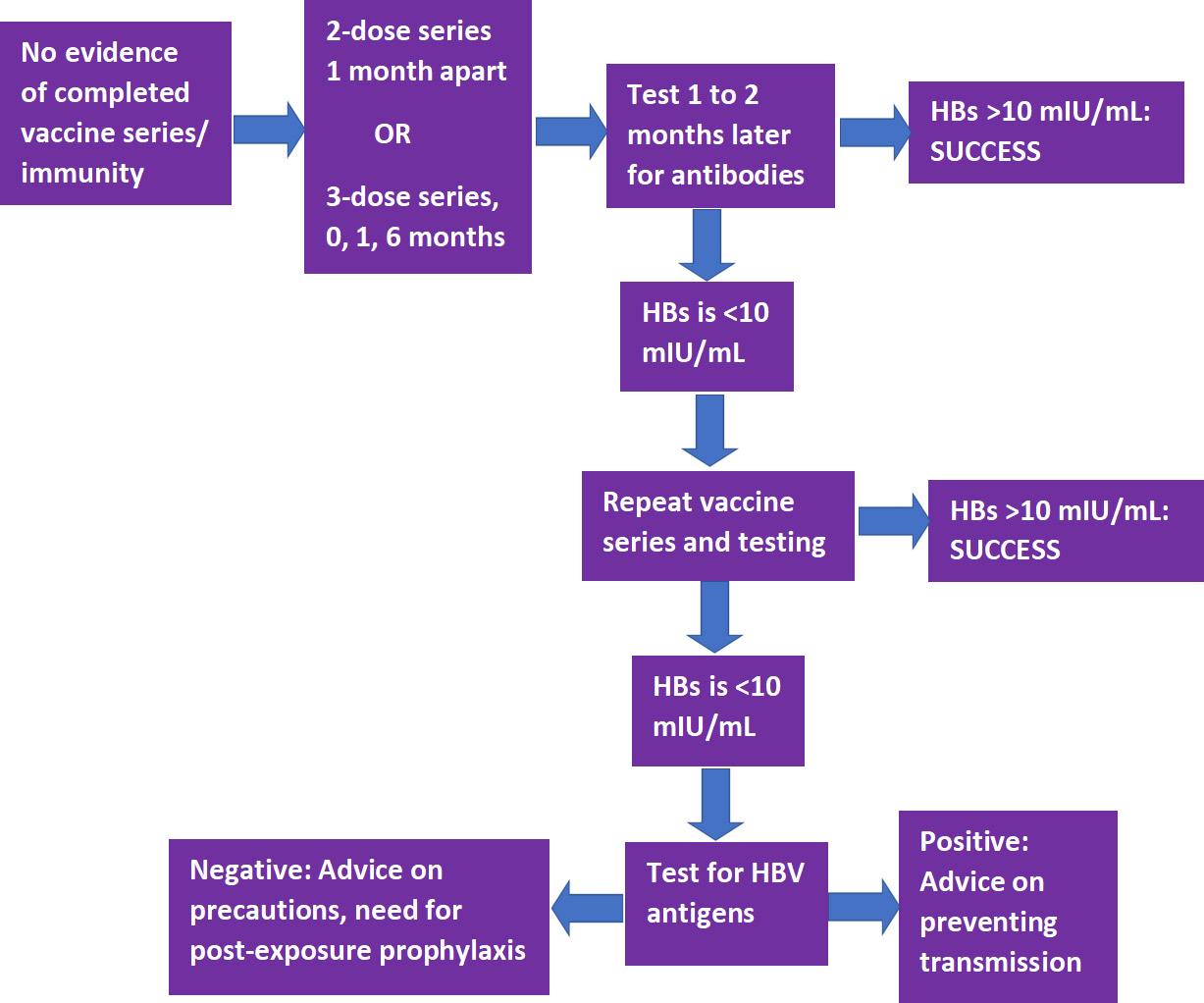

Following completion of a vaccine series, serological testing for Hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) should be performed 1 to 2 months later.3,11 If the level of anti-HBs is <10 mIU/mL, the individual should receive a second series and repeat serological testing. If testing still indicates an inadequate response, the individual is considered a ‘non-responder.’ Separate testing is then recommended to determine if the individual is positive for HBV antigens. If this test result is positive, advice should be provided on how to prevent transmission to others. If negative, advice should be given on precautions to take to prevent infection, and of the need for post-exposure prophylaxis should a confirmed/probable exposure occur. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Pathway for HBV vaccination and testing

Measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine

The recommendation for MMR immunization is based on age.11 For individuals born in 1957 or later, in the absence of prior MMR vaccination or serological evidence of immunity to measles or mumps, a 2-dose series of MMR vaccine with the doses at least 4 weeks apart is recommended (for rubella, a single dose is sufficient).11 During a mumps outbreak, a third dose of mumps-virus-containing vaccine is recommended for previously vaccinated at-risk individuals.12 Individuals born before 1957 are considered immune, while consideration should be given to vaccination for unvaccinated HCP if there is no laboratory evidence of disease or immunity to rubella (1-dose) or measles and/or mumps (2-dose), and during an outbreak of these diseases the respective 1- or 2-dose vaccination schedule is recommended.11 Women should not receive this vaccine while pregnant and should avoid becoming pregnant for 3 months following vaccination.13

Tetanus/Diphtheria/Pertussis (Td/Tdap) vaccine

Tdap as a single-dose vaccine is recommended if not previously received/unknown, even if Td was previously given.11 In addition, a Td/Tdap booster should be given every 10 years. Revaccination is recommended during each pregnancy.

Varicella vaccine

A 2-dose series (doses at least 4 weeks apart) is recommended for unvaccinated DHCP, those who have not had chickenpox/ no serological evidence of immunity.11 Women should not receive this vaccine while pregnant and should avoid becoming pregnant for 3 months following vaccination.14

Influenza

Annual immunization against influenza is recommended and generally given as inactivated vaccine administered by injection. Live attenuated influenza vaccine (administered nasally) or inactivated vaccine may be given to non-pregnant individuals below the age of 50.11 In addition, while it is unlikely that dental healthcare personnel would come in close contact with severely immunosuppressed patients requiring protective isolation, should this be the case then inactivated vaccine is preferred.

| Table 1. Recommended vaccines for DHCP | Contraindications | |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis B | 2-dose series 1 month apart or 3-dose series at months 0, 1 and 6. | A life-threatening allergic reaction to a previous dose of HBV vaccine.A severe allergy to any ingredient.Other contraindications can be found on National Vaccine Information Center (NVIC) website.15 |

| MMR | 2- dose series with doses at least 4 weeks apart if born 1957 or later. A third dose during an outbreak for at-risk previously vaccinated DHCP. Born prior to 1957 considered immune (see above). | A severe allergy to any ingredientPregnancy.Other contraindications can be found on the NVIC website.13 |

| Td/Tdap | Individuals who have not previously received Tdap should receive Tdap (even if had Td). Tdap/Td booster every 10 years. Revaccination during each pregnancy. | A severe allergic reaction to a previous dose of the vaccine.A severe allergy to any ingredient. Other contraindications can be found on the NVIC website.16 |

| Varicella | 2-dose series with doses at least 4 weeks apart for unvaccinated individuals or those who have not had chickenpox or without serological evidence of immunity. | A severe allergy to any ingredient.PregnancyOther contraindications can be found on the NVIC website.14 |

| Influenza | Annual immunization | A life-threatening allergic reaction to any previous flu vaccine.< 6 months of age should not receive the inactivated vaccine.Under age 2 years should not receive the live (nasal) vaccine.Other contraindications for the live (nasal) vaccine can be found on the NVIC website.17 |

| COVID-19 | All DHCP. 2-dose series for mRNA vaccines (see above). Believed an annual vaccination will be needed, pending information. | Individuals with severe allergies/allergies to an ingredient should discuss this with their physician. |

COVID-19

SARS-CoV-2 vaccines reviewed by the FDA and granted Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) are now available.18,19 It is critically important that immunization for as many people as possible occurs to combat the ongoing pandemic. The effectiveness of available vaccines based on mRNA technology (Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna) is ≥90%, substantially higher than that of annual influenza vaccines, and the results of clinical trials showed a good safety profile. A 2-f series is required, with the doses 21 and 28 days apart, respectively, for the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines.

For the initial roll-out, with a limited vaccine supply, the CDC issued guidance in December 2020 on prioritization for immunization based on a report from ACIP which advised that HCP be among those offered the first doses. ACIP also stated that federal, state and local jurisdictions should use this guidance for COVID-19 vaccination program planning and implementation. There was, however, concern that the advisory could be interpreted to exclude some categories of HCP, such as DHCP, based on different infection control guidelines for these groups.20 The CDC recommendations were therefore updated on December 29, 2020 and explicitly include prioritizing DHCP including students, and those other groups in Phase 1.21,22 Each State jurisdiction and county can determine prioritized groups for their vaccination program.

Recommendations and the Role of Dental Professionals

The CDC recommends that all dental settings develop a written health program that addresses immunizations, screening for tuberculosis, work restrictions and other occupational health needs.23 With respect to diseases for which immunization is recommended, DHCP with active measles/mumps/rubella/varicella or who are susceptible to any of these and were exposed are excluded from duty. For pertussis, DHCP are excluded for duty if they have active disease or were exposed and are symptomatic. Details on duty exclusion and its duration can be found in the CDC guidelines and recommendations, with the exception of COVID-19 for which guidance on quarantining was issued.3,24 In addition, a comprehensive written policy including a list of all recommended and required immunizations is recommended.The CDC recommends that all dental settings develop a written health program for DHCP that addresses immunizations, screening for tuberculosis, work restrictions and other occupational health needs.

Immunization of DHCP against specific communicable diseases as recommended by the CDC and ACIP reduces host susceptibility and also helps to reduce the potential for transmission to co-workers and patients.3 Dental professionals can further play a role in disease prevention by educating patients on the benefits of vaccination and by debunking misinformation25. It is especially important at the current time with respect to COVID-19 vaccines that key information is provided to patients regarding vaccine efficacy and safety to encourage vaccination. In addition, depending on the scope of practice for a given State, dental professionals may be able to administer vaccines.Dental professionals can further a role in disease prevention by educating patients on the benefits of vaccination and by debunking misinformation.

Scope of Practice

State laws dictate whether the scope of practice permits dental professionals to administer vaccines and, if so, which ones. The first State to permit dentists to immunize patients of all ages with many vaccine types was Oregon, after the Oregon House Bill 2220 was signed on May 6, 2019.26 The administration of vaccines by dentists is supported by the American Dental Association (ADA).27 A number of States now allow dentists to administer vaccines against COVID-19 during the current emergency.28 In Nevada, as of January 13, 2021 dentists and dental hygienists may administer COVID-19 vaccines with EUA and the State Board of Dental Examiners passed emergency regulations permitting licensed dental professionals to do so provided they first complete a required certification training program.29 Information on the ADA website can be found on vaccine allocation and administration by dentists for some States and contains links for further information.28 Requirements by State vary and may include, for example, additional training. Restrictions on where the vaccine may be administered must also be followed. It is critical to check with your State and State Board on the regulations for dentists and dental hygienists, and to ensure that all regulations and requirements are followed.It is critical to check with your State and State Board on the regulations for dentists and dental hygienists, and to ensure that all regulations and requirements are followed.

Conclusions

Recent events and the EUA of COVID-19 vaccines highlights the importance of immunization. Dental professionals can play a key role in helping to prevent disease transmission by following the recommendations, and educating patients on the benefits, efficacy and safety of vaccinations (in the absence of contraindications). In addition, where permitted and following regulations and recommendations, dental professionals can assist in the implementation of vaccination against COVID-19. Following the CDC recommendations on vaccinations is a key component of infection control and prevention and in protecting DHCP and patients.

Zircon Lab is America’s leading dental lab. We are partnered with dental offices nationwide and are consistently growing. As America’s highest quality dental lab with the most competitive pricing, the highest caliber of product, expert craftsmanship, and fastest delivery, we set the dental industry standard. After choosing Zircon Lab to be your dental lab of choice, you can trust our dental product will be unmatched by any competitors.

References

- 1.Andre FE, Booy R, Bock HL, Clemens J, Datta SK, John TJ et al. Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2008;86(2):81-160. Available at: https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/2/07-040089/en/.

- 2.CDC. Benefits from Immunization During the Vaccines for Children Program Era — United States, 1994–2013. MMWR April 25, 2014;63(16):352-5.

- 3.CDC. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings — 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(RR17);1–61.

- 4.CDC. Immunization of Health-Care Personnel: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 2011; 60(RR-7).

- 5.OSHA Fact Sheet. Hepatitis B Vaccination Protection. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/OshDoc/data_BloodborneFacts/bbfact05.pdf.

- 6.CDC. State Healthcare Worker and Patient Vaccination Laws. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/vaccinationlaws.html

- 7.Phadke VK, Bednarczyk RA, Salmon DA, Omer SB. Association Between Vaccine Refusal and Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in the United States: A Review of Measles and Pertussis. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1353.

- 8.Healthcare Training Leader. Carrot or Stick: Immunization Laws for Healthcare Workers, January 14, 2020. Available at: https://healthcare.trainingleader.com/2020/01/immunization-laws-for-healthcare-workers/.

- 9.Tufts School of Dental Medicine. Immunization & Health Insurance. Immunization Requirements. Available at: https://dental.tufts.edu/immunization-health-insurance.

- 10.The Ohio State University College of Dentistry. Immunization Requirements. Available at: https://dentistry.osu.edu/dental-hygiene/immunization-requirements.

- 11.CDC. Recommended Vaccines for Healthcare Workers. Updated 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adults/rec-vac/hcw.html.

- 12.CDC. Recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for Use of a Third Dose of Mumps Virus–Containing Vaccine in Persons at Increased Risk for Mumps During an Outbreak. MMWR 2018;67(1);33–38. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6701a7.htm.

- 13.National Vaccine Information Center. Who should not get Measles vaccine? Available at: https://www.nvic.org/vaccines-and-diseases/measles/who-should-not-get-measles-vaccine-mmr.aspx.

- 14.National Vaccine Information Center. Who should not get Chickenpox vaccine? Available at: https://www.nvic.org/vaccines-and-diseases/chickenpox/vaccine-who-should-not-get.aspx.

- 15.National Vaccine Information Center. Who should not get Hepatitis B vaccine? Available at: https://www.nvic.org/vaccines-and-diseases/hepatitis-b/vaccine-who-should-not-get.aspx

- 16.National Vaccine Information Center. Who should not get Tetanus vaccine? Available at: https://www.nvic.org/vaccines-and-diseases/tetanus/vaccine-who-should-not-get.aspx.

- 17.National Vaccine Information Center. Who Should Not Get the Influenza (Flu) Vaccines? Available at: https://www.nvic.org/vaccines-and-diseases/influenza/vaccine-who-should-not-get.aspx.

- 18.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA Takes Key Action in Fight Against COVID-19 By Issuing Emergency Use Authorization for First COVID-19 Vaccine. December 11, 2020. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-key-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-first-covid-19.

- 19.U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA Takes Additional Action in Fight Against COVID-19 By Issuing Emergency Use Authorization for Second COVID-19 Vaccine. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-additional-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-second-covid.

- 20.Coalition Letter, COVID-19 Vaccination Playbook for Jurisdictional Operations. December 16, 2020. Available at: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Advocacy/Files/201216_cdc_ncird_covid19_coalition.pdf.

- 21.CDC. The Importance of COVID-19 Vaccination for Healthcare Personnel. Updated December 28, 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/hcp.html.

- 22.https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2021-archive/january/cdc-confirms-dentists-in-first-phase-of-covid-19-vaccinations.

- 23.CDC. Dental Health Care Personnel Safety and Program Evaluation https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/summary-infection-prevention-practices/personal-safety-program-evaluation.html.

- 24.ADA. What to Do if Someone on Your Staff Tests Positive for COVID-19. Available at: https://success.ada.org/~/media/CPS/Files/COVID/A_Positive_COVID-19_Test_Result_On_Your_Staff.pdf?la=en.

- 25.Hotez P. America and Europe’s new normal: the return of vaccine-preventable diseases. Pediatr Res 2019;85(7):912-4. doi:10.1038/s41390-019-0354-3.

- 26.Oregon Health & Science University. Oregon Dental Immunization Resources. Available at: https://www.ohsu.edu/school-of-dentistry/oregon-dental-immunization-resources.

- 27.ADA News. ADA supports efforts allowing dentists to administer vaccines, October 23, 2020. Available at: https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2020-archive/october/ada-supports-efforts-allowing-dentists-to-administer-vaccines.

- 28.ADA. COVID-19 Vaccine Regulations for Dentists Map. https://success.ada.org/en/practice-management/patients/covid-19-vaccine-regulations-for-dentists-map.

- 29.Nevada Dental Hygienists’ Association. Not going to miss my shot. Available at: https://nvdha.com/.

Dental Impressions: The Digital Alternative

Dental impressions are defined as “a negative imprint of an oral structure used to produce a positive replica of the structure to be used as a permanent record or in the production of a dental restoration or prosthesis.”1

The concept of taking dental impressions to create dental models was first introduced in the mid-18th century when Phillip Pfaff, dentist to Frederick the Great of Prussia, described the technique of pouring plaster of Paris into a beeswax impression.2

While our materials have certainly evolved over the course of the last 260 years, we continue to follow a similar workflow in our attempt to create an accurate analog representation of the oral environment. This conversion process presents many challenges for practicing clinicians that are related to impression retake cost, time, patient comfort and frustration when errors lead to an ill-fitting final restoration. It is appropriate then to pose the question, why is the most critically important step in what we do in restorative dentistry, which is to transfer the data from the patient (dental impression) to the laboratory (gypsum model), continued to be captured in an analog manner when we have a viable digital alternative?

This analog dental impression workflow also creates complications for our dental laboratory partners that are perhaps best illustrated by a 2015 survey in which 47 percent of the survey respondents ranked dentists’ impression-taking skills as their number one client related challenge.3 The results of this survey are supported by an often cited 2005 article in the Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry which concluded that 89.1 percent of dental impressions sent to a dental laboratory had at least one or more observable, critical errors.4

Regardless of whether one chooses to replicate an oral structure digitally or in a more conventional manner, paying attention to the fundamentals of preparation design, tissue management and appropriate isolation is paramount. However, digital impressions address many of the concerns related to retake cost, time, patient comfort5 and, due to their accuracy,6,7 helps to reduce frustration when delivering the final restoration.

I am so proud to say that we are the first dental school in North America to have secured these recently introduced intraoral scanners for use by our students in the pre-doctoral clinics. I view these units as game changers that offer distinct advantages over conventional impressions, and with many intraoral scanner options available, there is no need to wait to join the early adopters as you can easily find one that meets your individual practice goals. Implementing this contemporary approach in capturing “positive” images of oral structures will certainly afford you the opportunity to improve your clinical outcomes while showcasing your interest and commitment to providing-state-of-the-art dentistry to your patients.

By Gary L. Stafford

Marquette University

Published version.WDA Journal,Vol. 93, No. 1 (January-February 2017): 17-18.

Publisher link. ©2017 Wisconsin Dental Association. Used with permission.

Zircon Lab is America’s leading dental lab. We are partnered with dental offices nationwide and are consistently growing. As America’s highest quality dental lab with the most competitive pricing, the highest caliber of product, expert craftsmanship, and fastest delivery, we set the dental industry standard. After choosing Zircon Lab to be your dental lab of choice, you can trust our dental product will be unmatched by any competitors.

Zirconia – Separating Fact From Fiction

ABSTRACT

The use and popularity of both zirconia and lithium disilicate have increased dramatically over the last several years (Fig. 1). In fact, if current trends hold1 it is entirely possible that that the escalating use of both zirconia and lithium disilicate will soon lead to the demise of traditional PFM’s. This article will focus specifically on zirconia.

Zirconia has many positive attributes not the least of which is high strength. In fact, the flexural strength of monolithic zirconia crowns can be anywhere from five to well over 10 times that of conventional PFM’s.2-4 Likewise, the fracture toughness (ability to resist crack propagation) of zirconia is significantly higher than both lithium disilicate and PFM restorations.5 In addition,

zirconia can be bonded or conventionally cemented, is very wear-friendly to opposing tooth structure when properly polished, is compatible with CAD-CAM technology, and can be used in the monolithic form to maximize strength or as a supportive substructure and layered with various ceramics to optimize esthetics. This article will focus on just what zirconia is, its advantages and disadvantages, recent improvements in optical properties, misconceptions some may have, how to optimize the zirconia surface prior to placement, and various cementation options.

What is Zirconia?

Zirconia is often referred to as “white metal” or “white steel”. This terminology may have originated with the introduction of razor-sharp zirconia knives used as cutlery with blades that are typically harder and more corrosive resistant than those of their steel counterparts (Fig. 2). Of course, zirconia is not steel. In fact, it is not even a metal. Zirconia is the oxide of the element zirconium (element 40 in the periodic table). While the element zirconium is a tough hard silvery white metal (Fig. 3) its oxide, the zirconia we use in dentistry, is not. Zirconium is not found in nature in its pure elemental form. It exists combined with other elements forming minerals such as zircon (ZrSiO4) and baddeleyite (mostly ZrO2). These and other minerals are mined, refined, and purified through a number of complex physical and chemical processes to produce zirconium oxide powder (ZrO2) (Fig. 4). This powder (a polycrystalline ceramic) can be shaped, pressed, and fully or partially sintered to create zirconia pucks and blocks (Fig. 5) that can be milled using CADCAM technology to create zirconia dental restorations and supporting frameworks.

Types of Zirconia

Zirconia exists in three distinct temperature and pressure dependent crystalline configurations or phases (monoclinic, tetragonal, and cubic). At normal temperatures and pressures zirconia exists in the monoclinic crystalline form. While this is the most stable configuration of zirconia it lacks the physical properties required for dental use. When heated to approximately 1170°C the monoclinic powdered form of zirconia will coalesce into a solid (sintering). During this process the zirconia crystals undergo a phase transformation from the monoclinic to the tetragonal crystalline configuration (Fig. 6). This form of zirconia is very strong, biocompatible, corrosion resistant, can be milled, and has the physical properties necessary for use as a dental restorative or supporting structure. When further heated to approximately 2,100°C another phase transformation occurs and the tetragonal crystals transform to the cubic crystalline configuration forming a very hard, translucent, and somewhat brittle

Zirconia Conundrums

One of the problems with the tetragonal form of zir- conia used in the fabrication of dental restorations is it is not inherently stable and readily converts back to its weaker, more stable, and lower energy state monoclin- ic crystalline form. Various dopants such as yttrium oxide (Y2O3) and aluminum oxide (Al2O3) are add- ed in very small amounts to stabilize the tetragonal crystalline lattice as well as modify optical properties. This so called “yttria-stabilized zirconia” is in fact, not entirely stable. It is actually “metastable” meaning that given the right conditions the tetragonal crystals can convert back into their monoclinic configuration.

On a small scale this is actually a desir- able property as it makes zirconia resistant to crack propagation via a property called transformation toughening. Simply stat- ed, as a crack is initiated on the zirconia surface and begins to propagate there is a localized conversion of the tetragonal crystals around the advancing crack front back into the monoclinic form. This re- sults in a localized volumetric expansion of the crystals (around 4%) surrounding the crack essentially compressing and sealing the defect and mitigating further crack advancement. So, on a small scale the metastable nature of zirconia can be a positive attribute due to transformation toughening.

However, on a large scale it can be a negative as excessive tetragonal to monoclinic phase transformation can weaken overall assembly strength po- tentially leading to catastrophic failure. Indeed, in the early part of this centu- ry thousands of Prozyr zirconia femoral heads (used in hip replacement surgery) were recalled due to numerous instances of spontaneous fracturing of the zirconia femoral heads within 27 months of place- ment (expected lifespan was at least 10 years). The failures were attributed in part to minute changes in processing tempera- tures during manufacture that resulted in excessive tetragonal to monoclinic phase transformation over-time.9-11 These fail- ures highlight the importance of using zirconia produced by reputable manufac- tures (all zirconia is not created equally).

To take full advantage of the physical properties of zirconia it makes sense to use them as full contour monolithic res- torations whenever possible. That is, to avoid layering or pressing ceramics over zirconia (as is often done to optimize esthetics) because the layering ceramic, along with the interface between the zir- conia and layered ceramic, are weak links in the restorative assembly. In addition, monolithic zirconia restorations that can be milled full contour keep costs low as no additional time is required for layer- ing by a ceramist. While high strength monolithic zirconia restorations make sense, esthetics can be an issue in the an- terior regions of the mouth where the in- herently high value and stark white color of some monolithic zirconia restorations, coupled with a lack of translucency and fluorescence, can make them unsuitable when optimal esthetics is required. The esthetics of monolithic zirconia has im- proved significantly in recent years with the introduction of so-called “translu- cent” zirconia. Manufacturers employ a number of techniques to improve the translucency of zirconia including reduc- ing grain size, reducing alumina content, modification of processing and pressing techniques, altering sintering times and temperatures, and manipulating dopant levels to increase the percentage of the more translucent cubic crystals relative to the more opaque tetragonal crystals.

Sandblasting Zirconia Prior To Placement

It is the author’s strong opinion that the zirconia surface should be particle abraded (sandblasted) prior to placement no matter what type of conventional or resin-based cement is used. There is significant sup- port in the literature for this recommen- dation.15-18 While there is some concern that sandblasting has the potential to in- duce surface and subsurface cracks and/or

defects that could reduce physical proper- ties19,20, the author is unaware of any stud- ies that demonstrate this to be a clinical problem assuming appropriate blasting pressures, particle types, and particle sizes are utilized. In fact, some studies found that sandblasting actually increases the flexural strength of zirconia (due to trans- formation toughening).12,21 Sandblasting zirconia is useful in terms of cleaning the target surface of impurities, increasing surface roughness and surface area, raising surface energy, improving the bond to zir- conia primers and adhesives, and generally optimizing the surface prior to bonding or conventional cementation.22 Having said this, the term “sandblasting” is very am- biguous. Sandblast with what exactly? At what pressure and distance? The general consensus among researchers and opinion leaders is that traditional high strength zirconia (3-4 mol% yttria concentration) can be safely and effectively sandblast- ed with 30-50 micron aluminous oxide (Al2O3) using a blast pressure of 1.5-2.8 bar (approximately 20-40 psi) from a dis- tance of 1-2 cm and for a duration of 10-20 seconds.18,23,24 In addition, some research- ers recommend the nozzle head be held at an angle of approximately 60 degrees.24 When dealing with translucent zirconia (5 mol% yttria concentration) that has a reduced capacity to undergo transforma- tion toughening, blasting pressures should be in the lower range (approximately 20 psi) to minimize any surface damage that could lead to a reduction in physical prop- erties. Burgess and McLaren have sug- gested using 50-micron silica glass beads as an alternative to harder aluminum ox- ide particles when sandblasting translu- cent zirconia.25 Their testing showed no reduction in the physical properties when glass beads were used. Additional testing is needed to confirm and refine optimal protocols for sandblasting both translucent and high strength zirconia.

As far as when to sandblast, the au- thor prefers to sandblast the intaglio sur- face of zirconia restorations after try-in and any adjustments, and just prior to

conventionally cementing or adhesively bonding the restoration into place. In this regard, the author strongly recom- mends that dentists invest in a quality chair-side sandblasting unit (i.e. Micro- etcher II, Danville Materials) and dust cabinet with a built-in fan filtration unit (i.e. Microcab, Danville Materials). If the dentist does not have a sandblaster then the author recommends having the dental laboratory sandblast the resto- ration just before shipment. Of course, this requires a high degree of faith that the dental lab is sandblasting the zirconia correctly. Once the zirconia restoration is ready for placement dentists have several important decisions to make: 1) Should the restoration be conventionally cement- ed or adhesively bonded into place? 2) Should a separate zirconia primer such as 10-Methacryloyloxydecyl Dihydrogen Phosphate (10-MDP) be applied at some point after sandblasting? 3) Is it necessary to clean the zirconia surface before ce- mentation with alkaline solutions such as Ivoclean (Ivoclar) or ZirClean (BISCO)?

Are Alkaline Cleaning Solutions Necessary Prior to Zirconia Primer Application?

It is the author’s strong opinion that if you want to predictably and durably bond to zirconia with resin-based cements then it must be sandblasted and a zirconia primer placed. The primer can take the form of a separately applied solution that contains a phosphate ester zirconia prim- er such as 10-MDP (i.e. Z-Prime/BIS-

CO, Monobond Plus/Ivoclar, Clearfil Ceramic Primer Plus/Kuraray, various universal adhesives22, etc.) or by using a resin cement that incorporates a zirconia primer directly in its chemical makeup (i.e. PANAVIA SA Cement Plus Ku- raray, Unicem 2/3M ESPE). A recent study found that 10-MDP zirconia primers chemically interact with the zir- conia surface by both hydrogen and ionic bonding mechanisms.26 This chemical interaction requires that terminal phos- phate groups in zirconia primer mole- cules such as 10-MDP (Fig.8)can freely interact with reactive sites on the zirconia surface. Zirconia has a remarkable affin- ity for phosphate ions.27 This affinity ex- tends not only to the phosphate groups in zirconia primers but also to phosphate groups and ions that are inherent in sa- liva. When zirconia restorations are tried in and the intaglio surface is contaminat- ed by saliva, the phosphate ions from the saliva bind to, and occupy, the same reac- tive sites that zirconia primers require for chemical interactions. This competition for reaction sites significantly decreases the efficacy of zirconia primers and it is necessary to “free-up” these sites so zir- conia primers can function optimally. This can be accomplished by sandblast- ing the restoration after saliva contami- nation and/or the use of strongly alkaline cleaning solutions such as Ivoclean (Ivo- clar Vivadent) or ZirClean (BISCO). It should be pointed out that vigorous rins- ing with water, or the use of acetone and alcohol, is not effective in cleaning zirco-

nia surfaces that have been contaminated with saliva.28 Products such as Ivoclean and ZirClean essentially work by hav- ing a higher affinity for phosphate ions than does the zirconia itself. In effect, the cleaning agent chemically scavenges phosphate ions from the zirconia surface and in so doing frees up reaction sites that now become available for chemical inter- action with subsequently placed zirconia primers. If the dentist is sandblasting the zirconia restoration themselves (after it is tried in and just prior to placement), then the use of a separate cleaning agent is not necessary (but still an option) as the sandblasting alone is sufficient in terms of freeing up reaction sites. If the den- tist does not have a sandblaster, and had the dental lab sandblast the restoration before shipment, then the restoration SHOULD be treated with a cleaning solution such as Ivolean or ZirClean (af- ter it has been tried in and prior to prim- er application). To reiterate, studies show that the best way to treat saliva-contam- inated zirconia surfaces is by sandblast- ing and/or the use of strongly alkaline cleaning solutions such as Ivoclean or ZirClean.29,30 Two last important notes:

1) While phosphoric acid (H3PO4) is an effective cleaning agent for saliva-con- taminated silica-based ceramics (such as stacked porcelain and lithium disilicate), it is contraindicated for cleaning zirconia surfaces. This is because, just as in the case of saliva, the phosphate ions from the phosphoric acid remain bound to the zirconia surface (even after rinsing) and tie-up reaction sites required for chemical interaction with zirconia primers. 2) While silane is an effective primer for sili-effective for priming zirconia sur- ate ester primers such as 10-MDP).

Cementing and Bonding Zirconia Restorations

The fact is there is not one specific universal protocol to use when it comes to the placement of zirconia restorations. The optimal way to treat both the zirconia and tooth surfaces prior to placement is con- tingent on many factors including, the specific clinical conditions, how retentive the preparation is, the nature of the conventional or resin-based cement being used, the minimum occlusal thickness, whether the dentist or the lab sandblasted the zirconia, the type of zirconia being placed (conventional vs. translucent), and esthetics (will the color of the cement affect the esthetic result). As previously discussed and as a general rule, the author recommends that the in- taglio surface of all zirconia restorations be particle abraded (sand- blasted) and a zirconia primer placed (typically a phosphate ester such as 10-MDP). However, this is not true in every situation and the use of a separate zirconia primer is actually contraindicated or not necessary with some materials. As an example, Ceramir C&B (DOXA Dental) is a “bioactive” glass ionomer/calcium aluminate hybrid cement that is very hydrophilic in nature. Hydrophilic sur- faces generally interface well with other hydrophilic surfaces (“like likes like”) but are generally less or non-interactive with hydropho- bic surfaces. For example, water (hydrophilic) does not mix well with oil (hydrophobic). Properly sandblasted zirconia has a high energy hydrophilic surface. Once a zirconia primer is placed the hydrophilic surface becomes hydrophobic (Fig.9). This is advan- tageous when using methacrylate-based resin cements that are also hydrophobic but can be a detriment with hydrophilic non-resin containing materials such as Ceramir C&B. Indeed, there are a number of anecdotal reports of zirconia crowns loosening or falling out when a zirconia primer was used prior to cementation with Ce- ramir C&B. For those dentists using Ceramir C&B, the zirconia surface should still be sandblasted to optimize surface conditions, but a zirconia primer should NOT be used.32 Likewise, conven- tional glass ionomer cements (i.e. Fuji II/GC, Ketac CEM/ 3M ESPE) do not require the use of a separate zirconia primer.

However, zirconia primers (i.e. Z-Prime, BISCO, Monobond Plus, Ivoclar) have been shown to increase bond strength of zir- conia to both RMGI33,34 and methacrylate based resin cements.35 RMGI (resin-modified glass ionomer) cements have many pos- itive attributes including good physical properties, low solubili- ty, some chemical bond to tooth structure, low film thickness, fluoride release, anti-microbial activity, good long-term clini- cal track record, and low incidence of postoperative sensitivity. Perhaps the biggest clinical advantages of RMGI cements is that they are very easy to mix, place, and clean. In fact, cement cleanup is generally much easier compared to resin cements, and this fact alone makes RMGI an attractive cementation option. Indeed, according to a 2018 survey of 1,026 dentists, RMGI cements (i.e. Rely X Luting Plus/3M, FujiCEM 2/GC) are currently the most popular cement type used in North America36 (Fig.10). The author personally considers RMGI to still be one of the best cementation options for high strength zirco- nia assuming the preparations have proper resistance and re- tention form and a minimum occlusal thickness of 1 mm or more. Even though studies appear to support the application of a separate zirconia primer after sandblasting to enhance the bond of RMGI to zirconia, the actual clinical relevance and benefit of this extra step is unclear and open for debate. The author’s personal preference, at least at this time, is to apply a separate zirconia primer (Z-Prime, BISCO) after sandblast- ing when cementing zirconia restorations with a RMGI. The author also recommends a warm air dryer be used to evaporate

primer solvents from the zirconia surface after primer application. Warm/dry air is simply very effective at removing solvent carriers and by “heating up” the substrate one can speculate that reaction rates will be accelerated, molecular interactions become more frequent, and greater num- bers of chemical bonds are formed.

In situations where there is a lack of resistance and retention form, esthetics is an issue, or maximum adhesion is re- quired, then self-etching self-priming resin-based cements (i.e. RelyX Unice- m/3M ESPE, Maxcem/Kerr, Bis-Cem/ BISCO, G-Cem/GC) or resin-based cements used in conjunction with a den-

tin bonding agent (i.e. Duo-Link/BIS- CO, RelyX Ultimate Adhesive Resin Cement/3M ESPE, Multilink/Ivoclar) are preferable over conventional ce- ments. Resin-based cements have a dis- tinct advantage over RMGI and other conventional cements when it comes to bonding restorations on, or in, minimal- ly retentive preparations as they bond more durably and predictably to both tooth tissues and zirconia. In addition, they may be a better choice when dealing with translucent zirconia or zirconia res- torations with minimal occlusal thick- ness as resin-based cements allow better stress distribution when loaded, may in-

hibit crack formation, and generally op- timize overall assembly strength.25 On the downside, resin-based cements can be difficult to clean, are more technique sensitive, and require extra steps when used in conjunction with a separately placed bonding agent. While dual cure self-etching self-priming resin cements are popular with dentists because they do not require a separate bonding agent be placed on the tooth, dentists should be aware that the highest bond to tooth structure is achieved by the use of res- in cements used in conjunction with a separately placed bonding agent.

In fact, some studies have found that even the self-etching/priming cements (such as Unicem 2) that are designed to be used without a separate bonding agent per- form better, in terms of bond strength to tooth structure, when a separate bond- ing agent is placed on the tooth first.37-39 There is some ambiguity as to the neces- sity of using a separate zirconia primer with some resin-based cements. This is because some self-etching resin cements such as Panavia SA Cement (Kuraray) and Unicem 2 (3M ESPE) already con- tain a phosphate ester zirconia primer inherent in their formulations. This may preclude the need for a separate dedicated zirconia primer. Indeed, some of these materials have shown promise bonding to both tooth tissues and zir- conia without using a separately placed adhesive or primer.40,41

CONCLUSION

A misconception held by many dentists is that “you cannot bond to zirconia.” The fact is you can bond very predictably and durably to zirconia surfaces using a com- bination of sandblasting, a phosphate ester primer such as 10-MDP, and an appropriate resin-based cement42-46 (Figs. 11-14).

The optimal way to treat zirconia and tooth surfaces prior to placement of zirconia restorations is contingent on many factors including, the specific clinical conditions, how retentive the preparation is, the nature of the conventional or resin-based cement being used, the minimum occlusal thickness, whether the dentist or the lab sandblasted the zirconia, the type of zirconia being placed (conventional vs. translucent), and esthetics (will the color of the cement affect the esthetic result). Proper management of both the zirconia substrate and tooth tissues is crucial for predictable and du- rable clinical outcomes. As a general rule the intaglio surface of all zirconia resto- rations be particle abraded (sandblasted) and a zirconia primer placed (typically a phosphate ester such as 10-MDP).

However, this is not true in every situation, and the use of a separate zirconia primer is contraindicated or not necessary with some materials. In this regard manufac- turer instructions and recommendations should be followed precisel for optimal results. It is incumbent on all clinicians to familiarize themselves with optimal cementation options and pro hen placing zirconia restorations.

About Dr Gary Alex, DMD

Dr. Alex attended Penn State University on an athletic scholarship where he graduated with a degree in Biology in 1977. He then took advanced level graduate courses in chemistry and biology before working at Jefferson Hospital in Philadelphia. He attended Tufts University Dental School where he earned his DMD in 1981. He has taken thousands of hours of continuing dental education over the last 35 years with an emphasis on occlusion, adhesion, comprehensive dentistry, materials, and esthetics.

Dr. Alex has researched and lectured internationally on adhesive and cosmetic dentistry, dental materials, comprehensive dentistry, and occlusion. He is an accredited member of the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry and past president of the AACD New York Chapter. With a background in chemistry and adhesive technology, he is a consultant for numerous dental manufacturers and member of the IADR (International Association of Dental Research). He has written and had published numerous scientific articles and papers and regularly conducts and participates in scientific studies on materials and adhesives. He has studied occlusion extensively with Dr. Peter Dawson (Center for Advanced Dental Study) and the late Dr. Bob Lee (Lee Institute) and is a member of the AES (American Equilibration Society). He has been the director of “PAC Live Ultimate Occlusion” and “Aesthetic Advantage Occlusion and Comprehensive Dentistry” programs. He is co-founder of the “Long Island Center for Advanced Dentistry” which provides the advanced continuing education training for dentists through lecture and hands-on programs. Dr. Alex is on the editorial board of, and has had a number of articles published in, the highly respected and peer-reviewed publications “Inside Dentistry“, “Compendium”, “Journal of Cosmetic Dentistry”, and “Functional Esthetics and Restorative Dentistry”. Dr. Alex is involved with a number of continuing education programs and regularly conducts hands-on programs and lectures on adhesion, porcelain veneers, direct and indirect restorations, materials, and occlusion. Dr. Alex maintains a busy fee for service practice in Huntington, NY, that is geared toward comprehensive prosthetic and cosmetic dentistry.

Zircon Lab is America’s leading dental lab. We are partnered with dental offices nationwide and are consistently growing. As America’s highest quality dental lab with the most competitive pricing, the highest caliber of product, expert craftsmanship, and fastest delivery, we set the dental industry standard. After choosing Zircon Lab to be your dental lab of choice, you can trust our dental product will be unmatched by any competitors.

References

- Makhija SK, Lawson NC, Gilbert GH, et al. Dentist material selection for single-unit crowns: findings from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Dent. 2016;55:40-47.

- Fischer J, Stawarczyk B, Hämmerle CH. Flexural strength of veneering ceramics for zirconia. J Dent 2008;3 6:316 – 321.

- Matsuzaki F, Sekine H, Honma S, Takanashi T, Furuya K, Yajima Y, Yoshinari. M. Translucency and flexural strength of monolithic translucent zirconia and porcelain-layered zirconia. Dent Mater 2015;34(6):910-917.

- Kayahan ZO. Monolithic zirconia: A review of the literature. Biomedical Research 2016;27(4):1427-1436.

- Ritzberger C, et al. Properties and Clinical Application of Three Types of Dental Glass-Ceramics and Ceramics for CAD-CAM Technologies. Materials 2010;3:3700-3713.

- Burgess JO, et al. Enamel Wear Opposing Polished and Aged Zirconia. Op Dent 2014:39(2):189-194.

- Daou EE. Esthetic Prosthetic Restorations: Reliability and Effects on Antagonist Dentition. Open Dent J 2015;9:473-481.

- Esquivel-Upshaw JF, et al. Randomized clinical study of wear of enamel antagonists against polished monolithic zirconia crowns. J Dent 2018 Jan;68:19-27.

- Piconi C, et al. On the fracture of a zirconia ball head. J Mat Science: Materials in Medicine 2006;17:289-300.

- Chevali J. What Future for Zirconia as a Biomaterial? Biomaterials 2006 (Feb);27(4):535-543

- Brown SS, Green DD, Pezzotti G, Donaldson T K, Clarke IC. Possible triggers for phase transformation in zirconia hip balls. J. Biomed. Mater 2008;85(2): 444-452.

- McLaren EA, Lawson N, Choi J, et al. New high-translucent cubic-phase-containing zirconia: clinical and laboratory considerations and the effect of air abrasion on strength. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2017;38(6):e13-e16.

- Burgess J, et al. When Placing Zirconia or Lithium Disilicate Restorations, want factors govern your decision to employ traditional cementation or bonding protocols? Inside Dent August 2018 pages 52-53.

- Kwon SJ, Lawson NC, McLaren EE, Nejat AH, Burgess JO. Comparison of the mechanical properties of translucent zirconia and lithium disilicate. J Prosthet Dent. 2018 Jul;120(1):132-137.

- Kim BK, Bae HE, Shim JS, et al. The influence of ceramic surface treatments on the tensile bond strength of composite resin to all-ceramic coping materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2005;94:357–362.

- Yi YA, Ahn JS, Park YJ, et al. The Effect of Sandblasting and Different Primers on Shear Bond Strength Between Yttria-tetragonal Zirconia Polycrystal Ceramic and a Self-adhesive Resin Cement. Operative Dentistry: January/February 2015;40(1):63-71.

- Barragan G, Chasqueira F, Arantes-Oliveria S, Portugal J. Ceramic repair: influence of chemical and mechanical surface conditioning on adhesion to zirconia. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2014;13(2)155-158.

- Zandparsa R, et al. An in-vitro comparison of shear bond strength of zirconia to enamel using different surface treatments. J Prosthodont 2014;23(2):117-123.

- Zhang Y, Lawn BR, Rekow DE, Thompson VP. Effect of sandblasting on long-term performance of dental ceramics. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2004;71(2):381-386.

- Chintapalli RK, Marro FG, Jimenez-Pique E, Anglada M. Phase transformation and subsurface damage in 3Y-TZP after sandblasting. Dent Mater. 2013;29(5):566-572.

- Ozcan M, Melo R, Souza RO, et al. Effect of air-particle abrasion protocols on the biaxial flexural strength, surface characteristics and phase transformation of zirconia after cyclic loading. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2013;20:19-28.

- Alex G. Universal Adhesives: The next evolution in adhesive dentistry? Compendium 2015;36(1):15-28.

- Hallmann L, et al. Effect of blasting pressure, abrasive particle size and grade on phase transformation and morphological change of dental zirconia surface. J Prostet Dent 2016;115(3): 341-349.

- Personal communication Dr. Nasser Barghi (The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Dental School at San Antonio, Texas), Dr. Byoung Suh (Chemist and president BISCO Inc).

- McLaren E, Burgess J, Brucia J. Cubic-Containing zirconia: Is adhesive or conventional cementation best? Compendium 2008;39(5):282-284.

- Nagaoka, N. et al. Chemical interaction mechanism of 10-MDP with zirconia. Sci. Rep. 2017;30(7):45563; doi: 10.1038/srep45563.

- Xubiao L, et al. Enhancement of Phosphate Adsorption on Zirconium Hydroxide by Ammonium Modification. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2017 56 (34), 9419-9428.

- Yang B, Lange-Jansen HC, Scharnberg M, et al. Influence of saliva contamination on zirconia ceramic bonding. Dent Mater.2008;24(4):508-513.

- Chen L, Suh BI, Shen H. Minimize the contamination of zirconia restoration surface with saliva [abstract]. J Dent Res. 2013;92(spec iss A). Abstract 1654.

- Khan AA, et al. Recent Trends in Surface Treatment Methods for Bonding Composite Cement to Zirconia: A Review. Journal of Adhesive Dentistry 2017;19(1):7-19.

- Alex G. Preparing porcelain surface for optimal bonding. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2008;29(6):324-335.

- Information confirmed via E-Mail with Dr. Jesper Loof Tekn, CEO and Executive VP Operations and Research and Deveopement–Doxa Dental.

- Alnassar T, Ozer F, Chiche G, Blatz MB. Effect of different ceramic primers on shear bond strength of resin-modified glass ionomer cement to zirconia. J Adhesive Science and Tech 2016;30(22):2429-2438.

- Liang Chen PhD–Head Chemist, BISCO Inc.–Personal communication.

- Kobes KG, Vandewalle KS. Bond strength of resin cements to zirconia conditioned with primers. Gen Dent. 2013;61(6):73-76.

- Clinicians Report (CR) 2018;11(3):1-3.

- Barcellos DC, Batista GR, Silva MA, et al. Evaluation of bond strength of self-adhesive cements to dentin with or wihout application of adhesive systems. J Adhes Dent. 2011;13(3):261-265.

- Chen C, He F, Burrow MF, et al. Bond strengths of two self-adhesive resin cements to dentin with different treatments. J Med Biol Eng. 2011;31(1):73-77.

- Pisani-Proença J, Erhardt MC, Amaral R, et al. Influence of different surface conditioning protocols on microtensile bond strength of self-adhesive resin cements to dentin. J Prosthet Dent. 2011;105(4):227-235.

- Koizumi H, Nakayama D, Komine F, et al. Bonding of resin-based luting cements to zirconia with and without the use of ceramic priming agents. J Adhes Dent. 012;14(4):385-392.

- Personal conversation via Email with Dr. Reinhold Hecht, Division Scientist–Research & Development, 3M Oral Care.

- Yi YA, Ahn JS, Park YJ, et al. The effect of sandblasting and different primers on shear bond strength between yttria-tetragonal zirconia polycrystal ceramic and a self-adhesive resin cement. Oper Dent. 2015 Jan-Feb;40(1):63-71.

- Barragan G, Chasqueira F, Arantes-Oliveria S, Portugal J. Ceramic repair: influence of chemical and mechanical surface conditioning on adhesion to zirconia. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2014;13(2)155-158.

- Zandparsa R, Talua NA, Finkelman MD, Schaus SE. An in-vitro comparison of shear bond strength of zirconia to enamel using different surface treatments. J Prosthodont. 2014;23(2):117-123.

- Kern M. Bonding to oxide ceramics-laboratory testing versus clinical outcome. Dent Mater. 2015;31(1):8-14.

- Tanis MC, Akay C, Karakis D. Resin cementation of zirconia ceramics with different bonding agents. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2015;29(2):363-367.

Cloud-Based Dental Software Helps Practices Adapt to The New Normal

Since the American Dental Association began tracking the impact of COVID-19 on dental practices in March 2020, there has been a slow and steady climb towards normalcy.

But we’re not there yet, based on research from January 2021. According to the survey, 32.3% of practices were open and back to business as usual. 66.7% were open but experiencing lower patient volume than usual. Clearly, the road ahead could be long for many practices.

During the early days of the pandemic, many dentists felt overwhelmed as they weighed their options, seeking information on the new regulations for PPE, FFCRA, FMLA, and more. When they received approval to re-open, they had to determine how best to keep their patients, staff, and themselves safe while running a profitable business. This entailed reevaluating their entire workflow, including the practice management software.

Cloud-Based Dental Practice Management Software Front and Center

Unlike other medical segments, dentistry has been slower to adopt cloud-based software. While it is fair to say that the majority of dentists believe that the cloud is the future, approximately 85% were still hanging on to their server-based software as COVID-19 hit in Spring 2020. With limited access to their system and patient data during the shutdown, more practices than ever considered the benefits of the cloud, and many made the move.

Curve Hero™, Curve Dental’s cloud-based dental practice management software, experienced a significant spike in product demos during COVID-19. During the first few months of the pandemic, nearly three times as many practices moved to Curve’s cloud-based platform than normal. In February 2021, Curve announced that over 33,000 dental professionals used Curve Hero, far more than any other cloud-based provider.

Remote Access to Data Helped Curve Hero Customers Get a Jump Start on Recovery

Early on, Curve customers found how much easier it was to open their practice’s doors to their patients while using the Curve Hero platform. Practices made digital forms available to patients whose information automatically went directly into their Curve Hero database. Office staff informed patients of the practice’s COVID-19 protocols in advance of appointments which increased confidence in their commitment to keeping everyone safe. Billing went through the Patient Portal, eliminating the need to handle and return credit cards at the front desk. This “low-touch/no-touch” experience made a very challenging process far more manageable and safe than practices using traditional server-based systems.

What New Customers Said After Switching to Curve Hero

Going into the demo, dental professionals knew that cloud-based software allowed them much easier access to patient data than their server-based system. But they discovered many more benefits available with Curve Hero. Typically, dentists and office managers are reluctant to change software because of the anticipated disruption to their practice due to the data conversion process, a potential lengthy learning curve, and time-consuming training.

During product evaluations, they learned that Curve makes it significantly easier to switch software by having proven processes in place to make the transition as smooth as possible. Curve collaborates with the dental office from start to finish — during the initial setup through data review and final assembly. Curve has successfully completed more than 4,000 data, file, and image conversions from well over 90 practice management software products, both server-based and cloud-based. Watch Dr. Jesse Ritter explain his Curve Hero conversion experience in this video.

Web-based training means your team doesn’t have to travel. Staff adopts the software quickly because Curve separates each training session into small digestible bites. Plus, your staff has access to Curve Community, a rich library of information to remind them of what they learned or act as a quick training refresher.

Curve’s New Patient Engagement Feature Makes Practices Even More Productive

Recently, Curve added Curve GRO™, a patient engagement feature that simplifies and streamlines communications by having everything in a single system. Powered by a robust campaign engine, Curve GRO automatically manages patient reminder campaigns and updates the schedule when the patient confirms. For patients who may need to change their appointment or ask questions, GRO delivers 2-way conversational texting. For patients who do not respond to the reminder campaigns, GRO can automatically create tasks in the Smart Action List, allowing the staff to collaborate in real-time to triage patient outreach. A rules-based campaign engine combined with the Smart Action List is significant for dentistry because it creates automation, enforces best practices as determined by the practice administrator, and delivers an auditable trail of all activity that occurs.

Disasters Aren’t Planned. They Just Happen.

Well before COVID-19, dental practices have had to deal with unexpected events like fires, floods, data breaches, and more. If your data is contained on a server in your office and disaster strikes, you could be out of luck. There are so many good reasons to move your practice to the cloud starting with protecting your data. In addition, as we learned during the early stages of COVID-19 with the mandatory office shutdown, the ability to access data remotely to triage dental emergencies and manage rescheduling, billing, and payments were extremely beneficial to Curve customers and their patients. The cloud is by far your best option to protect your business from the unexpected.

About Curve:

Founded in 2004, Curve Dental provides web-based dental software and related services to dental practices within the United States and Canada. The company strives to make dental software less about computers and more about user experience. Curve’s creative thinking can be seen in the design of software that is easy to use and built only for the cloud. Visit www.curvedental.com for more information.

Zircon Lab is America’s leading dental lab. We are partnered with dental offices nationwide and are consistently growing. As America’s highest quality dental lab with the most competitive pricing, the highest caliber of product, expert craftsmanship, and fastest delivery, we set the dental industry standard. After choosing Zircon Lab to be your dental lab of choice, you can trust our dental product will be unmatched by any competitors.

The influence of soft-tissue volume grafting on the maintenance of peri-implant tissue health and stability

Abstract

Background

To investigate the influence of soft-tissue volume grafting employing autogenous connective tissue graft (CTG) simultaneous to implant placement on peri-implant tissue health and stability.

Material and methods

This cross-sectional observational study enrolled 19 patients (n = 29 implants) having dental implants placed with simultaneous soft-tissue volume grafting using CTG (test), and 36 selected controls (n = 55 implants) matched for age and years in function, who underwent conventional implant therapy (i.e., without soft-tissue volume grafting). Clinical outcomes (i.e., plaque index (PI), bleeding on probing (BOP), probing depth (PD), and mucosal recession (MR)) and frequency of peri-implant diseases were evaluated in both groups after a mean follow-up period of 6.15 ± 4.63 years.

Results

Significant differences between test and control groups at the patient level were noted for median BOP (0.0 vs. 25.0%; p = 0.023) and PD scores (2.33 vs. 2.83 mm; p = 0.001), respectively. The prevalence of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis amounted to 42.1% and 5.3% in the test and to 52.8% and 13.9% in the control group, respectively.

Conclusion

Simultaneous soft-tissue grafting using CTG had a beneficial effect on the maintenance of peri-implant health.

Introduction

A major goal of implant therapy is to ensure long-term peri-implant tissue health and create appealing esthetics. To obtain these therapeutic endpoints, soft-tissue grafting procedures performed either simultaneously with or after implant placement have become an indispensable part of contemporary implant dentistry [1].

From a biological point of view, a lack of or reduced height (< 2 mm) of keratinized mucosa (KM) around the implants was shown to jeopardize self-performed oral hygiene measures, which subsequently increased the likelihood of soft-tissue inflammation [1, 2]. As a consequence, soft-tissue grafting procedures aimed at increasing keratinized tissue have been shown to markedly improve peri-implant soft-tissue inflammatory conditions and were associated with higher marginal bone levels compared to the control sites [3]. Moreover, from an esthetic perspective, the presence of KM > 2 mm was demonstrated to be a preventive measure for the occurrence of peri-implant soft-tissue dehiscences [4].

Changes in peri-implant soft-tissue height, particularly on the facial aspect, are a critical factor that may compromise the overall esthetic result of implant-supported restoration [5]. A thin mucosa (also known as a soft-tissue biotype) at the time of implant installation was found to be a crucial component that correlated with facial soft-tissue recession [6,7,8]. In fact, to attenuate the undesirable changes of the soft-tissue margin, soft-tissue volume augmentation at the time of implant placement was also suggested as a preventive measure [9, 10]. On the contrary, currently available data evaluating procedures to increase mucosal thickness did not show any significant effects on bleeding scores, but higher interproximal marginal bone levels over time when compared with control sites [1]. Due to a lack of reporting, an evaluation of the prevalence of peri-implant disease was not feasible [1].

Therefore, the aim of the present cross-sectional analysis was to assess the influence of soft tissue volume grafting on the peri-implant tissue health and stability.

Materials and methods

The present investigation was designed as an observational, cross-sectional case–control study evaluating the clinical treatment outcomes of implants inserted simultaneously with (test group) and without (control group) soft-tissue volume augmentation. All patients had received the same implant brand (Ankylos®, Dentsply Sirona Implants, Hanau, Germany) in a single university clinic (Department of Oral Surgery and Implantology, Goethe University, Frankfurt) and were recruited during their yearly maintenance visits.

Patients were included in the study once they were informed about the investigation procedures and gave their written informed consent. The procedures in the present study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013, and the study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (registration number: 78/18).

Patient selection criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied for patient selection:

– Patients with > 18 years of age rehabilitated with at least one Ankylos® implant;

– Patients with treated chronic periodontitis and proper periodontal maintenance care;

– Non-smokers, smokers and former smokers;

– A good level of oral hygiene as evidenced by a plaque index (PI) < 1 at the implant level; and

– Attendance of yearly routine implant maintenance appointment.

Patients were excluded for the following conditions: the presence of combined endodontic–periodontal lesions; systemic diseases that could influence the outcome of the therapy, such as diabetes (HbA1c > 7), osteoporosis and antiresorptive therapy; a history of malignancy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or immunodeficiency; and pregnancy or lactation at the last follow-up.

Surgical protocol

Soft-tissue biotype was assessed preoperatively based on the probe’s transparency at the mid-facial aspect and categorized as thin when the probe was visible and thin when it was not visible. Two-piece platform-switched implants were placed 2–3 mm subcrestally according to the manufacturer’s surgical protocol. Implants in the control group exhibited a thick soft-tissue biotype and therefore underwent a conventional placement protocol (i.e., without soft-tissue volume grafting; Fig. 1a).

Implants in the test group presented with a thin soft-tissue biotype, and therefore, a connective tissue graft (CTG) harvested from the hard palate was simultaneously applied on the facial aspect via tunneling technique (Fig. 1b and Fig. 2). All surgeries were performed by one experienced oral surgeon (PP).

Implant and implant-site characteristics

The following study variables were assessed for the test and control implant sites: (1) implant age (i.e., defined as time after implant placement), (2) implant location in the upper jaw, and (3) implant diameter.

Clinical measurements

The following clinical parameters were registered at each implant site using a periodontal probe: (1) plaque index (PI) (Löe et al., 1967); (2) bleeding on probing (BOP)—measured as presence/absence; (3) probing depth (PD)—measured from the mucosal margin to the probable pocket; (4) mucosal recession (MR)—measured from the restoration margin to the mucosal margin; and (5) keratinized mucosa (KM) (mm)—measured on the buccal aspects of the implants.

PI, BOP, PD, and MR measurements were performed at six aspects per implant site: mesiobuccal (mb), midbuccal (b), distobuccal (db), mesiooral (mo), midoral (o), and distooral (do). KM measurement was performed at three aspects per implant site: mesiobuccal (mb), midbuccal (b), and distobuccal (db).

The presence of peri-implant diseases at each implant site was assessed as follows [11]:

- Peri-implant mucositis defined as the presence of BOP and/or suppuration with on gentle probing with or without increased PDs compared to previous examinations and an absence of bone loss beyond crestal bone level changes resulting from initial bone remodeling.

- Peri-implantitis defined as the presence of BOP and/or suppuration on gentle probing, increased PDs compared to previous examination, and the presence of bone loss beyond crestal bone level changes resulting from initial bone remodeling.

Radiographs (i.e., panoramic) were just taken when clinical signs suggested the presence of peri-implant tissue inflammation (i.e., the presence of BOP). To estimate the bone level changes at the respective implant sites, these radiographs were compared with those taken following the placement of the final prosthetic reconstruction (i.e., baseline).

Investigators meeting and calibration

Prior to the start of the study, a calibration meeting was held with each examiner (KO, AB, AR) to standardize (pseudonymous) data acquisition and the assessment of study variables. For the calibration of the examiners, double measurements were performed with a 5-min interval of the assessed clinical parameters in 5 patients with a total of 15 implants. The calibration was acceptable when repeated measurements were similar > 95% level. The documentation of demographic study variables, implant sites’ characteristics, and clinical measurements were documented using a generated standardized data extraction template.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using a commercially available software program (SPSS Statistics 27.0: IBM Corp., Ehningen, Germany). Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, medians and 95% confidence intervals) were calculated for mPI, BOP, PD, and MR values. The analysis was performed at the patient and implant levels. The data were tested for normality by means of the Shapiro-Wilk test. Comparisons of clinical parameters between the test and control groups were performed by employing the Mann-Whitney U test. Linear regression analyses were used to depict the relationship between mean BOP, PD, and MR values and KM scores. The alpha error was set at 0.05.

Results

Patient and implant sites’ characteristics

The test group included 19 patients (13 women and 6 men) with a total of 29 implants, whereas the control group included 36 patients (20 women and 16 men) with a total of 55 implants. Mean patient age in the test and control groups was 46.24 ± 18.48 and 62.21 ± 14.41 years, respectively. The mean implant functioning time was 4.16 ± 2.06 years for the test group and 7.19 ± 5.25 years for the control group. All implants in the test group revealed a diameter of 3.5 mm with an equal distribution between all regions investigated. In the control group, the most frequent diameter was also 3.5 mm (85.5%), with a predominant implant location in the region of the lateral and central incisors (Table 1).Table 1 Patient and implant site characteristicsFull size table

Clinical measurements

The results of the clinical measurements are presented in Table 2. In general, test and control groups were commonly characterized by low median PI scores at both patient (0.00 vs. 0.21; p = 0.093) and implant levels (0.17 vs. 0.17), respectively.Table 2 Clinical parameters (mean ± SD, median and 95% CI)Full size table

Marked differences between test and control groups were noted for median BOP scores, reaching statistical significance at the patient level (0.0 vs. 25.0%; p = 0.023).

Similarly, the test group was associated with markedly lower median PD values at both patient (2.33 vs. 2.83 mm; p = 0.001) and implant levels (2.33 vs. 2.83 mm), respectively.

Both groups revealed comparable median MR values at both patient (0.0 vs. 0.0 mm; p = 0.76) and implant levels (0.0 vs. 0.0 mm), respectively (Table 2).

Prevalence of peri-implant diseases

The frequency distribution of peri-implant diseases in the test and control groups at patient and implant levels is summarized in Tables 3 and 4.Table 3 Prevalence of peri-implant disease (patient level)Full size tableTable 4 Prevalence of peri-implant disease (implant level)Full size table

According to the given case definitions, 66.7% of the patients in the control group and 47.4% of the patients in the test group were diagnosed with peri-implant diseases. In the test group, the prevalence of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis amounted to 42.1% and 5.3%. In the control group, the corresponding values were 52.8% and 13.9%, respectively (Table 3).

At the implant level, the prevalence of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis amounted to 44.8% and 3.4% in the test group, and 52.7 and 9.1% in the control group, respectively (Table 4).

Regression analysis